Where Have All the Eiders Gone?

Identifying demographic bottlenecks and habitat use to support the recovery and management of American Common Eider: a range-wide, full life-cycle telemetry project

Eider hen. Photo by Emile David

Project Number: 162

Investigators: Scott Gilliland (Adjunct Researcher at Acadia University and Retired Biologist for Canadian Wildlife Service; ), Mark Mallory, Nic McLellan, Greg Robertson, Jean-François Giroux, Oliver Love, Al Hanson, Kelsey M. Sullivan, Lucas Savoy, Christine Lepage, Sarah Gutowsky

Focal Species: American Common Eider (Somateria mollissima dresseri)

Note: Project Investigators and the Sea Duck Joint Venture will gladly make the tracking and movement data resulting from this project available for environmental assessment and planning, other management-related needs, and addressing additional research questions. Please contact Kate Martin, SDJV US Coordinator, at or Scott Gilliland at for inquiries.

Eider hen. Photo by Emile David

The Story

Common Eiders are a long-lived, marine coastal species. There are four recognized subspecies in North America: Pacific, Northern, Hudson Bay, and American. The American Common Eider (Somateria mollissima dresseri) is known to breed on islands from the south-central coast of Labrador to Massachusetts, and winters from Newfoundland to New York. In the spring, they migrate north to breeding habitats on small islands, islets, and coastal habitats south of the Arctic ice. Eiders are also an important harvest species, popular across North America for sport and sustenance. The rise in popularity of eider harvest ultimately led to widespread declines of the species, eventually spurring one of North America’s earliest successful waterfowl conservation movements.

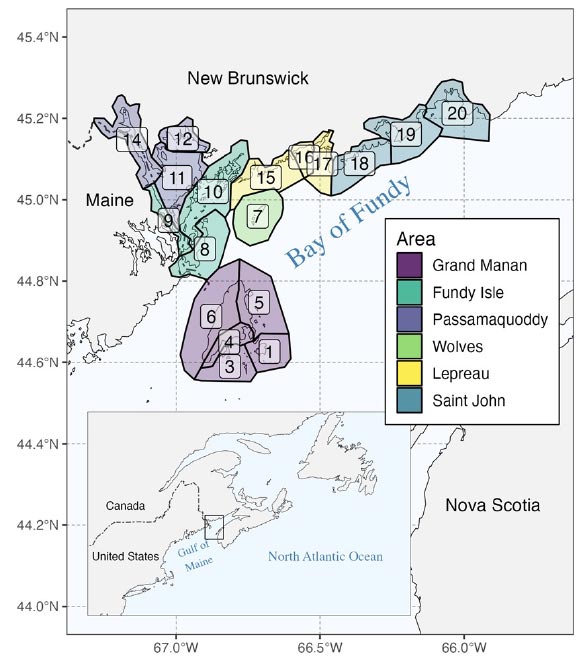

18 CWS coastal survey blocks overlapping spring aerial surveys for male American Common Eider in the Bay of Fundy, New Brunswick, Canada (from Gutowsky et al. in review)

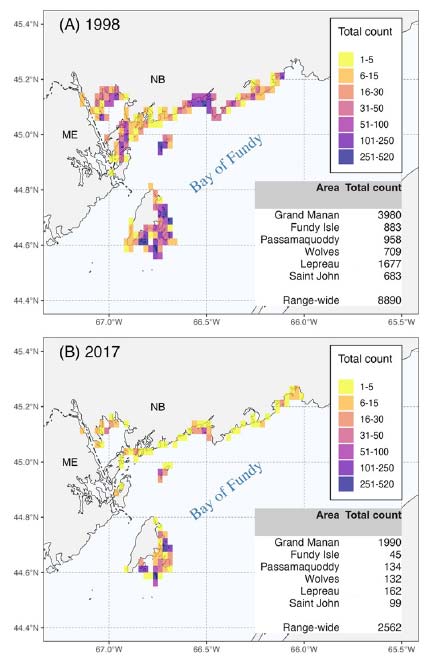

(A) Past (1998) and (B) recent (2017) distribution and abundance of male American Common Eider on spring aerial surveys in the Bay of Fundy, New Brunswick, Canada (from Gutowsky et al. in review)

By the end of the 19th Century, the exploitation of American Common Eiders had reduced their population to very small numbers. The outlook for the eiders was so dismal that a moratorium on the harvest of eiders was imposed following the promulgation of the Migratory Bird Treaty Act of 1918. Eiders responded well and continued to recover, and the moratorium was lifted, allowing harvest to be regulated for the next 60 – 70 years. With their recovery, eiders were once again a dominant feature along the coastlines of the New England states and Atlantic Canada. However, by the early 21st century, resource managers working on eiders in Massachusetts, Maine, Nova Scotia, and New Brunswick were once again noticing declines in eiders breeding, molting, and wintering across the southern part of their breeding range. Additionally, monitoring programs in New Brunswick showed a steep decline in the number of eiders breeding in the southwestern Bay of Fundy (Bowman et al. 2015), and banding operations in southwestern Nova Scotia and Maine were shut down as eiders abandoned molting sites. By 2012, aerial surveys conducted in Atlantic Canada suggested steep declines in the number of eiders wintering in New Brunswick and Nova Scotia (Gutowsky et al. 2023). Unfortunately, recent analyses of aerial survey data from breeding areas in New Brunswick up to 2019 show that the declines have continued at an alarming rate, amounting to a loss of nearly 10% per year over the past two decades (Gutowsky et al. in review). Analyses of information from the large-scale banding programs suggested these declines were widespread including important breeding areas in Nova Scotia and Maine (Giroux et al. 2021).

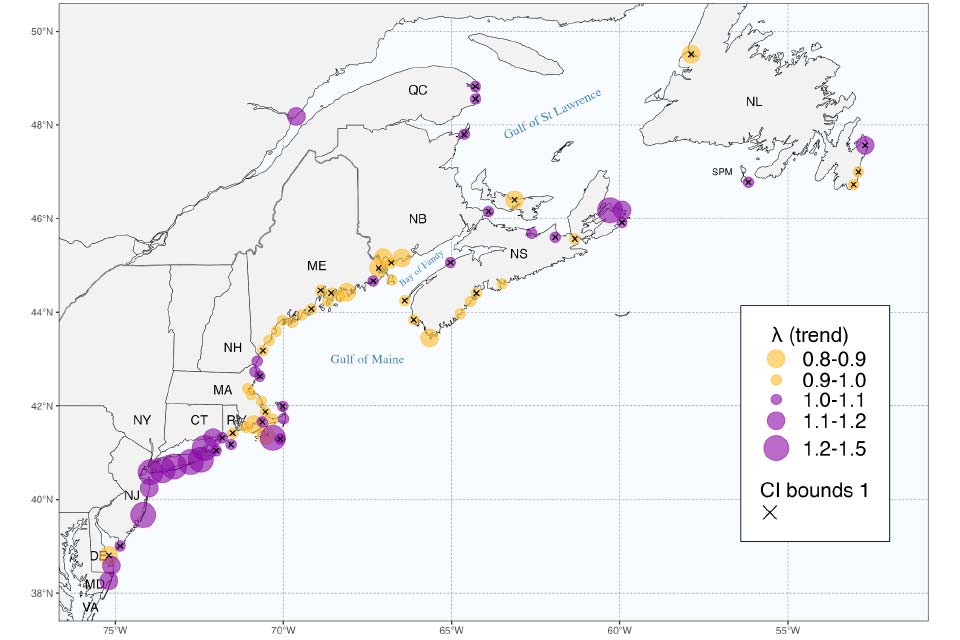

Common Eiders on ice. Photo: Emile David

Responding to increasing concern and a lack of comprehensive information about American Common Eiders, waterfowl managers and researchers gathered at a workshop in 2019 to consolidate what was known about the status, trends, and threats of the subspecies. Experts agreed there is considerable variation in numbers across the range, but overall eiders were increasing in the north (Quebec, Newfoundland, and Labrador) and declining in the south (Maine, New Brunswick, Nova Scotia). Recent quantitative findings confirm these suspected spatial patterns in trends; analyses of Christmas Bird Count data revealed consistent and widespread declines in local abundance throughout the entire Gulf of Maine and surrounding ecosystems, from Nova Scotia to Massachusetts, suggesting a large-scale redistribution away from the center of the overwintering range (Gutowsky et al. 2023).

Spatial distribution of localized trends of Common Eider on 76 Christmas Bird Count (CBC) circles from 2000-2020. Color of the trend estimate indicates direction of change and size indicates magnitude of change. Trend estimates with confidence intervals bounding one are identified by an “X,” indicating relative stability (from Gutowsky et al. 2023)

These changes are hypothesized to be caused by the rapid warming of ocean waters from the Gulf of Maine north to Labrador. Warmer ocean temperatures affect the distribution and quality of prey species like blue mussels, which are a critical food source for eiders, and enable the expansion of invasive species such as green crabs, disrupting marine ecosystems and food webs. Together, these changes are likely reducing the quality of eider habitats in some areas, resulting in changes in eider distribution and/or abundance. These concerns and resulting conversations led to a collaborative, multi-organization, multi-year research project funded in part by the Sea Duck Joint Venture.

The Project

Beginning in 2021, a research team including federal, state, provincial, academic, and non-profit partners deployed Argos satellite transmitters in adult female eiders in major breeding areas, to improve their understanding of breeding propensity and population connectivity and identify key habitats for the species. Tags have been deployed in major breeding areas in Maine, New Brunswick, Nova Scotia, Newfoundland, southern Labrador, and the St. Lawrence Estuary, Québec – all areas of distributional change for the species. The researchers also set out to estimate body condition and breeding propensity across their range, identify the timing of mortality for adult females, and identify key habitat and ecosystem changes in their range. This information will not only give insight into the population dynamics, it’s also being used to inform harvest limits and regulations, marine planning, restoration, and protections.

The Data

In addition to climate change impacts on marine habitats, there are a variety of other anthropogenic-driven threats to eiders. Rapidly expanding fisheries and aquaculture on the Atlantic coast may alter habitats, impacting access to key resources. Offshore wind development and other industrial activities may further displace birds or cause mortality through pollution and collisions. Up-to-date movement data from marked birds can be used for spatial planning, response and preparedness, and developing mitigation techniques to minimize the effects of human activities.

Collaboration with Hunters: Banding

The main way researchers have tracked not only Common Eiders but many other waterfowl species is through banding programs. Over time, hunters have contributed significantly to research by reporting bands recovered on harvested birds, along with location information, and sometimes samples. This collaboration has allowed scientists to gain unprecedented insight into many species’ migratory patterns, survival rates, and life histories.

While hunters still play a significant role in contributing to research through reporting recovered bands, eider distributional trends are changing far too quickly to document with band recoveries, which collect data over decades, to uncover new distributional patterns fully and efficiently. This is where the Argos global satellite system comes into play. Satellite tracking devices continuously send signals to the satellite system that provides immediate, real-time data and locations of the birds as they move and travel around for 2-3 years after attachment without the need to recover the bird. But to attach or embed the tracker, first, you have to catch the birds.

The Partners

As you can probably imagine, catching over 150 female Common Eiders across multiple states and provinces is not an easy feat. Over the past three years, alongside partners from the Canadian Wildlife Service, Science & Technology, Ducks Unlimited Canada, Duvetnor, University of Windsor, Acadia University, Université du Québec à Montréal, Nunatukavut Government, Biodiversity Research Institute, the Maine Department of Inland Fisheries and Wildlife, the University of Rhode Island, and Rhode Island Division of Fish & Wildlife, Scott Gilliland and his research team tagged 201 adult females.

This process also involved very careful handling and insertion of the tracking devices by seasoned veterinarians, who have been working with the team since the 90’s.

Alongside their research, the team worked with videographer Emile David to produce videos about the project. Each video covers a different aspect of the project, but for a more comprehensive look, watch the longer documentary video below:

Next Steps

In the summer of 2024, project partners plan to capture and mark additional eiders in Quebec in collaboration with Parks Canada. In addition, the Nunatsiavut government, in northern Labrador, is leading the capture and tagging of eiders to uncover movements, habitat use, and threats of eiders nesting in their region.

Media

- What goes on in a duck’s head? Researchers get closer to answer, CBC News, 2023

- Eider duck populations are declining. Both sides of the border want to know why, CBC News, 2022

- Grand Manan woman makes gruesome discovery while walking beach at low tide, CBC News, 2022

- More dead ducks wash up on Grand Manan shore, CBC News, 2022

- The Race to Save East Coast Eiders, Wildfowl Magazine, 2019

Project Reports

Interim Report FY21

Interim Report FY22

Interim Report FY23

Interim Report FY24

Interim Report FY25

Related Publications

Allen, R.B., McAuley, D.G., & Zimmerman, G.S. (2019). Adult Survival of Common Eiders in Maine. Northeastern Naturalist, 26(3), 656–671. https://www.jstor.org/stable/26860559

Bowman, T.D., Silverman, E.D., Gilliland, S.G., & Leirness, J.B. (2015). Status and trends of North American sea ducks: reinforcing the need for better monitoring. In Savard, J-PL., Derksen, D.V., Esler, D., Eadie, J.M. (ed) Ecology and conservation of North American sea ducks. CRC Press, New York, NY

Giroux, J.-F., Patenaude-Monette, M., Gilliland, S.G., Milton, G.R., Parsons, G.J., Gloutney, M.L., Mehl, K.R., Allen, R.B., McAuley, D.G., Reed, E.T. & McLellan, N.R. (2021). Estimating Population Growth and Recruitment Rates Across the Range of American Common Eiders. Journal of Wildlife Management, 85: 1646-1655. https://doi.org/10.1002/jwmg.22122

Gutowsky, S., Robertson, G.J., Mallory, M.L., McLellan, N.R. & Gilliland, S.G. (2023). Redistribution of wintering American Common Eiders (Somateria mollisima dresseri). Avian Conservation and Ecology 18(2):8. https://doi.org/10.5751/ACE-02510-180208

Gutowsky, S., Mallory, M.L., McLellan, N.R., Robertson, G.J., Connor, K., & Gilliland, S.G. (in review). Severe declines of male American Common Eiders (Somateria mollisima dresseri) during spring over the past two decades in the southwestern Bay of Fundy, Canada. Wildfowl.

Noel, K., McLellan, N., Gilliland, S. et al. (2021). Expert opinion on American common eiders in eastern North America: international information needs for future conservation. Socio-Ecological Practice Research 3, 153–166 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s42532-021-00083-6

Milton, G.R., Iverson, S.A., Smith, P.A., Tomlik, M.D., Parsons, G.J. & Mallory, M.L. (2016). Sex-specific survival of adult common eiders in Nova Scotia, Canadian Journal of Wildlife Management, 80: 1427-1436. https://doi.org/10.1002/jwmg.21135

Partners

Acknowledgements

This work could not be done without field and veterinary assistance from many people, including:

Maine 2021

Field work: Dustin Meattey, Brad Allen, Chris Dwyer, Jay Osenkowski, Chris Persico, Helen Yurek, Bill Hanson, Tim Welch, Logan Route, Emily Fellows, Tori Mezebish-Quinn, Tristen Burgess

Veterinary care: Glenn Olsen

Quebec 2021

Field work: Francis St. Pierre, Manon Souris, Jean-Francois Giroux, Sylvain Dorey

Veterinary care: Stéphane Lair, Marion Jalenques, Juliette Raulic

New Brunswick 2022

Field work: Dustin Meattey, Chris Persico, Logan Route, Helen Yurek, Sarah Wong

Veterinary care: Glenn Olsen, Juliette Raulic

Nova Scotia 2022

Field work: Stephanie Avery-Gomm, Asha Grewal, Lee Millett, Josh Cunningham, Mark Maddox, Kristine Hanifen, Jessie Wilson

Logistics: Manon Souris, Calvin D’Entremont

Veterinary care: Stéphane Lair, Julie Pujol, Judith Viau

Newfoundland 2022

Field work: Devon Dyson, Asha Grewal, Josh Cunningham, Mark Maddox, Kristine Hanifen, Jessie Wilson

Veterinary care: Marion Jalenques, Julie Pujol, Benjamin Jakobek

Logistics: Wayne Barney, Kirk Chambers, Lewis Huskins from Huskins Fisheries Limited, and the lobster fishermen from the wharfs at Forbes Point, NS and Foresters Point, NL who shared their stories about eiders and tended to the security our boats while left at the wharf and our crews when we were on the water.

Nova Scotia 2023

Field work: Lee Millett, Ryan Johnstone, Shane Keegan, Emile David

Logistics: Monan Sorais, Calvin D’Entremont

Veterinary care: Glenn Olsen, Kathleen MacAulay

Labrador 2023

Field work: Devon Dyson, Rich Martin, Emile David

Veterinary care: Stéphane Lair, Benjamin Jakobek , Judith Viau

Québec 2024

Field work: Francis St-Pierre, Manon Sorais, Adam Desjardins, Scott Gilliland, Al Hanson, Omer Nolin

Logistics: Christine Lepage, Marie-Claude Roy

Veterinary Care: Stéphane Lair

Rhode Island 2024

Field work: Tim Welch, Helen Yurek, Emily Fellows, Logan Route, Chris Persico, Jim Tappero, Jenny Kilburn, Tori Mezebish-Quinn, Scott McWilliams, Steve Bradfield, Gabby DeMillion, Jake Brown, Richard Mercer, Lizzi Bonczek, Dylan Bakner, Morgan Lucot, Jonathan Fiely, Paul Triolo, Shannon Wesson, Megan Gray, Keegan Foster

Veterinary care: Glenn Olsen, Lindsay Dwyer