Sea ducks can be a difficult species to study. From their remote breeding sites to their long-distance migrations, frequent movements, and use of many habitats, they can be hard to find, and even more difficult to monitor.

For years, scientists have approached sea duck population monitoring partially through aerial surveys using small planes and observers. In these surveys, an experienced scientist scans the water from a small plane flying close to the water’s surface, counting flock sizes and identifying species, if possible.

One of the planes that the Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife (WDFW) uses to complete aerial imagery surveys. Photo: Kate Martin

In places like the San Francisco Bay, these surveys provide a critical look into waterfowl populations. Many species use the bay and other estuaries along the Pacific as overwintering spots, and the open bay provides a centralized location for near-shore surveys. Since 1955, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS) and collaborators have conducted mid-winter aerial surveys here to evaluate species distribution and estimate population abundance to understand sea duck and other waterfowl species responses to oil spills, energy development, weather patterns, and other changing conditions.

In recent years, the USFWS moved away from conducting these surveys, and the USGS, along with other partners, has taken on the role of conducting and improving them. Many factors contribute to the overall shift away from aerial observer surveys – the surveys require small, low-flying planes, which present safety and logistical issues and are costly to use. Further, differences in methodology, observers, and experience level can cause data bias and differences in the detection probability of the birds.

Researchers Dr. Susan De La Cruz and Ms. Tanya Graham, alongside a coalition of partners in Washington state, USGS Western Ecological Research Center, the SDJV, and more, shared about how they are working to standardize survey methods along the entire West Coast as part of an SDJV-funded research project. Dr. De La Cruz is a research wildlife biologist with USGS, where for 30 years her work has focused on habitat, migration, and foraging ecology of sea ducks and waterbirds. Ms. Graham has been a biologist with the USGS Western Ecological Research Center for 15 years, where she manages wetland restoration and monitoring projects in addition to supporting aerial mid-winter survey efforts since 2012.

The main goals of the project are to develop a standardized aerial photographic survey for the Pacific Coast that will identify sea ducks within waterfowl flocks. Focal species include the Barrow’s Goldeneye, Harlequin Duck, Long-tailed Duck, Black Scoter, Surf Scoter, and White-winged Scoter. To do this, the team will use a standardized digital aerial survey that automates bird counts from aerial imagery using a previously developed mathematical model. This approach maximizes safety and will improve data consistency and model accuracy, leading to better estimates of sea duck abundance and species composition at key sites on the Pacific Coast.

Rather than building a new model, they will modify an existing one initially developed by Dr. Josh Adams of USGS and his colleagues for seabirds, so a large part of the project will be retraining the model to identify sea duck shapes using new photos. Sea ducks are often larger than seabirds and differ more in color, wing shape, and size, which will help make them easier to identify. Setting up the survey cameras on the planes is also a delicate art. Biologists at the Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife have researched and tested camera mount angles, ideal elevations for the plane, and how to maximize photo area coverage without overlapping images and counting birds twice.

Left: Plane camera setup mid-flight. Photo: Tanya Graham

Right: Joe Evenson showing the camera and imaging setup inside a WDFW plane. Photo: Kate Martin

Thus far, the team has completed two sets of imaging flights, in December 2024 and February 2025, collecting over 84,000 images. The Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife is also collecting imagery to help train the model. To date, they have run over 31,000 images through the first pass of the model. The team then uses these photos to train, correct, and retest the model. For each photo, both biologists and the model count the number of birds observed and separate them into groups – dabbling ducks, diving ducks, and sea ducks. By surveying areas with a diversity of species, flock sizes, and habitats, they strengthen the model and can continue to improve it over time. They have completed training with 30,000 photos and are working through the next set. In addition to training the new model, they are also still completing the traditional observer surveys, flying the same transects as before to continue the ongoing dataset as they test the new image-based surveys.

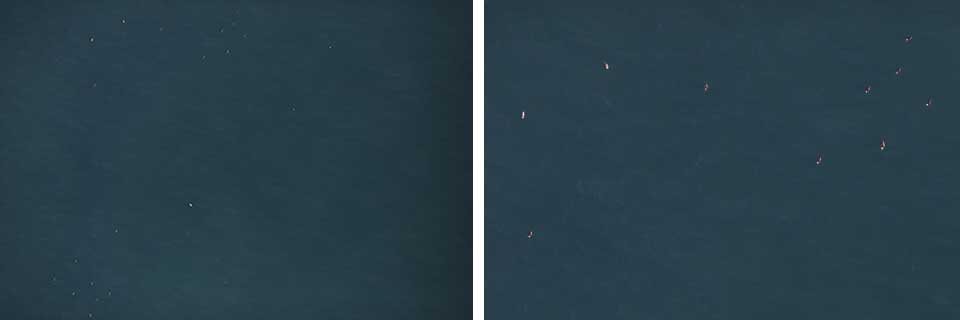

Left: Aerial survey photo taken in Monterey Bay, CA, on February 21, 2024. A flock of scoters is visible in the upper left corner of the photo. Photo: Tanya Graham. Right: Zoomed-in portion of the photo to the left, to showcase the image quality and the flock of scoters.

Improved survey methods mean more reliable and accurate population estimates for these elusive birds. Due to survey difficulties, there is little understanding of what fraction of sea duck populations rely on habitats on the coast outside of estuaries. These new methods will help remedy this and provide baseline data and monitoring for potential wind turbine projects, in the face of oil spills and other disasters, and for conservation planning by Migratory Bird Habitat Joint Ventures in the region.

There are around two years left of the project, primarily focused on taking photos and refining the model. Both Dr. De La Cruz and Ms. Graham emphasized how critical collaboration has been to the success of this project – no one group could complete these surveys and rebuild the model alone. Only through working with state, federal, NGO, and other partners have they been able to accomplish this large-scale project.

A global unified survey model and methodology are key products of this project. But outside of this, the team is also forming an advisory group with partners to better understand survey needs, use cases, and future directions and plans to conduct additional surveys in the Salish Sea and San Francisco Bay, two key sea duck sites. At completion, the team will have developed a standardized digital aerial survey methodology, an extensive public, annotated image library, and a fine-tuned model for Pacific Flyway sea ducks. We can’t wait to see how the rest of the project unfolds! You can learn more about the project and see project update reports here.